The Walking Dead Ends Unexpectedly

The Walking Dead issue 193 is worthy of a Hugo Awards nomination next year. It is a conclusion to the comic sprung entirely by surprise on the readership. To keep it under wraps, they solicited fake issues 194, 195 and 196 and made issue 193 a giant-sized finale at the regular price. Orders for those fake issues have been refunded.

The Walking Dead issue 193 is worthy of a Hugo Awards nomination next year. It is a conclusion to the comic sprung entirely by surprise on the readership. To keep it under wraps, they solicited fake issues 194, 195 and 196 and made issue 193 a giant-sized finale at the regular price. Orders for those fake issues have been refunded.

Without spoiling the content, it's a time jump that is intriguingly ambiguous about the proper lesson to take from the zombie apocalypse. I often find Robert Kirkman's writing to be heavy on obvious dialogue that could go unsaid, but the story he's told in 193 is effective. There's one particular moment between two sons that will stick with me for a while. The art is exceptional, including some multi-page spreads that are as good as anything Charlie Adlard has ever done.

Kirkman ends the comic with a multi-page essay explaining the decision to end the story and the reason he did it so abruptly without the marketing hype and massive orders that would've come from announcing it many issues in advance. (The short answer is that he hates knowing when the end of a book, movie or TV series is coming because it lessens the impact.)

In the essay he concludes by thanking a lot of people. Surprisingly, one of them is original series artist Tony Moore, who was engaged in a seven-year legal battle with Kirkman involving the rights to the comic before they reached a confidential settlement in 2012.

Review: 'Eternity Road' by Jack McDevitt

This post-apocalyptic novel occurs long after the fall of civilization. Humans in an agrarian society along the Mississippi River yearn to learn more about the Roadmakers, so named because of the enormous network of roads left behind. Little else survives other than six books and a lot of garbage impervious to decay. Ten years after a quest to learn more ends in tragedy, the lone survivor's death leads to a discovery in his belongings. This sparks a dangerous new quest by a small band to cross the continent and find a legendary place where civilization endured.

This post-apocalyptic novel occurs long after the fall of civilization. Humans in an agrarian society along the Mississippi River yearn to learn more about the Roadmakers, so named because of the enormous network of roads left behind. Little else survives other than six books and a lot of garbage impervious to decay. Ten years after a quest to learn more ends in tragedy, the lone survivor's death leads to a discovery in his belongings. This sparks a dangerous new quest by a small band to cross the continent and find a legendary place where civilization endured.

Jack McDevitt's novel is a love letter to the importance of books. The best moments see the protagonists puzzle over ancient objects and places they encounter. The pacing is pokey until it races to a last-third payoff resolving the core mystery in a satisfying way. Seeing humans grapple with ways to invent better engines for river travel reminded me of Philip José Farmer's Riverworld, another work that venerates human ingenuity.

Review: 'Every Crooked Path' by Steven James

When my favorite stop on I-95 in North Carolina ceased selling paperbacks because the distributor folded, they offered to sell me the spinrack and the 24 well-thumbed books left on it. I ended up with some thrillers I otherwise would have missed, like this one. I love the rack but wish I'd missed this book.

When my favorite stop on I-95 in North Carolina ceased selling paperbacks because the distributor folded, they offered to sell me the spinrack and the 24 well-thumbed books left on it. I ended up with some thrillers I otherwise would have missed, like this one. I love the rack but wish I'd missed this book.

Every Crooked Path is a convoluted novel with slapdash pacing, thin characterization and characters who speak in the same voice -- a trait most excruciating when the protagonist attempts to bond across the generation gap with his girlfriend's sullen 15-year-old daughter. FBI agent Patrick Bowers is hunting a dark web child sex trafficking group, a disturbing subject the author tries to soften by being short on harrowing details. That works, but the logic of the case doesn't. One thing that did work was a character suffering a breakdown from a job watching videos of child exploitation for a safety group. That has become an all-too-real problem for social media moderators at Facebook.

Behind the Throne by K.B. Wagers

This book was highly recommended by six avid readers on File 770 and they were right. Hailimi Mercedes Jaya Bristol, a gunrunner who left her family 20 years ago and never looked back, is brought home when the assassinations of her sisters and niece leave her heir to the empire.

This book was highly recommended by six avid readers on File 770 and they were right. Hailimi Mercedes Jaya Bristol, a gunrunner who left her family 20 years ago and never looked back, is brought home when the assassinations of her sisters and niece leave her heir to the empire.

The story mixes palace intrigue with well-spun action as Haili struggles to survive long enough to figure out who's behind the attempted coup. The India-inspired, far-future society Wagers has created is richly drawn and contains surprises too good to spoil. A lot of the charm comes from the fact that Haili's accomplished criminal life made her a fish out of water as a potential empress. She's always clashing with her ever-present bodyguards over her desire to carry her own weapons and is sometimes less the protected than the protector.

One minor criticism is that the large cast of characters around Haili made it tough to remember them all when they showed up again. The novel is a fantastic opener to a trilogy.

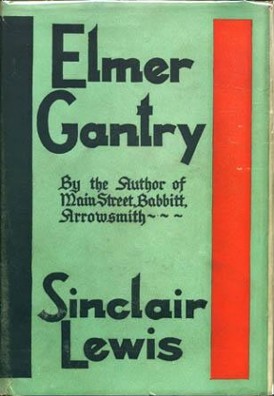

Elmer Gantry by Sinclair Lewis

Elmer Gantry felt as if I'd read it already because the protagonist has been so widely referenced in American culture. Sinclair Lewis mercilessly skewers a narcissistic preacher who exploits Christianity to enrich himself and secretly commits every sin he fulminates against from the pulpit.

Elmer Gantry felt as if I'd read it already because the protagonist has been so widely referenced in American culture. Sinclair Lewis mercilessly skewers a narcissistic preacher who exploits Christianity to enrich himself and secretly commits every sin he fulminates against from the pulpit.

The book begins with Gantry as a hard-partying, anti-intellectual football star at a Baptist university, follows him into a career as a pastor he feels no calling to pursue and tracks for a quarter century his ups and downs (but mostly ups). Gantry's mistreatment of women, whom he adores until he gets them, was particularly cutting. Aside from some racial slurs and Gantry's brief flirtation with a 14-year-old girl being insufficiently called out as predatory, the book has aged well.

Lewis is a withering social critic. Elmer Gantry is less a biography than an indictment. It's rare to read a book about a character so disliked by its author. I've never wanted more to see a protagonist pay for his sins.

Gamer Fantastic RPG Fiction Anthology

This anthology doesn't live up to the inventive premise of telling stories where roleplaying games and reality intersect. I was ready to quit after the introductory material and early stories all hammered the same worn-out joke about gamers being slovenly fast-food addicts, but I stuck around to see what Jim C. Hines would do with his story "Mightier Than the Sword." His entertaining tale was about libriomancers who could pull weapons and creatures out of SF/F novels, a premise he later expanded into a book of that name. I liked his references to real writers and novels, including a subtle, self-deprecating joke about himself. Reading Jody Lynn Nye's engaging "Roles We Play" about roleplaying being used as a therapeutic tool in the 19th century has motivated me to seek out her novels. Kristine Kathryn Rusch ended with an intriguing story about a magical RPG store in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. The rest was forgettable, including a short perfunctory tribute to E. Gary Gygax after his death.

This anthology doesn't live up to the inventive premise of telling stories where roleplaying games and reality intersect. I was ready to quit after the introductory material and early stories all hammered the same worn-out joke about gamers being slovenly fast-food addicts, but I stuck around to see what Jim C. Hines would do with his story "Mightier Than the Sword." His entertaining tale was about libriomancers who could pull weapons and creatures out of SF/F novels, a premise he later expanded into a book of that name. I liked his references to real writers and novels, including a subtle, self-deprecating joke about himself. Reading Jody Lynn Nye's engaging "Roles We Play" about roleplaying being used as a therapeutic tool in the 19th century has motivated me to seek out her novels. Kristine Kathryn Rusch ended with an intriguing story about a magical RPG store in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. The rest was forgettable, including a short perfunctory tribute to E. Gary Gygax after his death.

Star Wars: Rebel Dream by Aaron Allston

As a fan of Aaron Allston going back to his earliest RPG designs for Car Wars and Champions in the 1980s, I liked this book but felt like his creativity was constrained by the plot requirements required of the 12th book in a 19-book series (which I haven't read prior to this installment). The novel follows the fall of Coruscant to the Yuuzhan Vong. Starfighter squadrons and Jedi commanded by Wedge Antilles must take and hold the planet Borleias to help Coruscant refugees escape and regroup. Luke, Leia, Han, Lando, Mara Jade Skywalker and Jaina Solo participate in dogfights and one covert mission to set up book 13. Most of the novel's appeal was seeing familiar faces engaged in expected derring-do, but the Yuuzhan Vong are as appealingly weird a foe as The Borg in Star Trek. They loathe tech and instead rely on pervasive and sadistic bioengineering. My favorite scenes were told from their perspective. Allston, who died in 2014 at age 53, was one of the best media tie-in writers in SF/F.