Mister Mystery: Why Papers Keep Using Honorifics

This paragraph in a Wall Street Journal story on Lance Armstrong does a nice job of demonstrating why I hate the use of honorifics such as "Mr." on second reference in news stories:

Mr. Armstrong's Austin lawyer, Mr. Herman, called Mr. Tygart and offered to dispatch Mr. Armstrong's legal team to Colorado to meet with him. Mr. Tygart said he wanted Mr. Armstrong to come. When Mr. Herman pushed back, Mr. Tygart called the meeting off.

This practice has been dying out in American newspapers, but the New York Times is keeping it alive, though with some weird rules. Osama Bin Laden was Mr. Bin Laden in the paper for a while, but now like Hitler and Stalin he gets to be more readable in news stories than the average mister or missus.

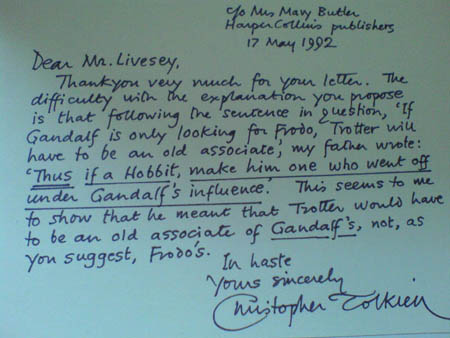

Christopher Tolkien Hates the Peter Jackson Movies

Christopher Tolkien, the son of J.R.R. Tolkien, gave his first interview to the media last year after being his father's literary executor for four decades. Speaking to the French newspaper Le Monde, the 87-year-old expressed great unhappiness with the Peter Jackson movies even though they helped sell 25 million copies of the books in three years, a 1,000 percent increase:

Invited to meet Peter Jackson, the Tolkien family preferred not to. Why? "They eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25," Christopher says regretfully. "And it seems that The Hobbit will be the same kind of film."

This divorce has been systematically driven by the logic of Hollywood. "Tolkien has become a monster, devoured by his own popularity and absorbed into the absurdity of our time," Christopher Tolkien observes sadly. "The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work, and what it has become, has overwhelmed me. The commercialization has reduced the aesthetic and philosophical impact of the creation to nothing. There is only one solution for me: to turn my head away."

I grew up reading Tolkien and eagerly attended the first Lord of the Rings movie. I haven't seen the rest yet, but the original film did not cheapen the books, which were full of action that appealed to young readers. When I was a teen, I did not devour The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings because of their "seriousness," though I suspect I would value that upon a rereading. I don't see how any movie or TV adaptation could damage the experience of reading the book on which it's based, particularly an enduring classic like the novels of Tolkien. The words are still there in the proper order.

Amazingly, the studio that made Jackson's films told Tolkien's estate they didn't make any money -- so it wasn't entitled to a cut of profits. "We were receiving statements saying that the producers did not owe the Tolkien Estate a dime," said Cathleen Blackburn, an attorney for the estate.

I hope the accountants were mumbling "my precioussssss" to themselves as they cooked the books.

AP Launches News Archive Going Back to '70s

Associated Press has quietly launched a beta of the AP News Archive, a free searchable database of AP news stories that goes back as far as 1974. The archive comprises at least 1.5 million articles at present, based on the approximate number of results returned in a Google search of the domain apnewsarchive.com.

The AP touts the archive as being more accurate than that dodgy, not-to-be-trusted Internet:

If you've tried to do historical research online, you know that there's a lot of misinformation floating around the Internet. It can be time-consuming, to say the least, to comb through dozens of sites and search results to find the information you're looking for.

Imagine that instead, you could find accurate, reliable historical information quickly and easily, all on one site, and all up to the highest standards of journalism.

Though the archive stretches back decades, I had trouble finding subjects I'd expect to be there -- such as the Drudge Retort's fair use copyright dispute with AP five years ago. I'm not in the database at all, which hurts.

I did find a few stories that my wife Mary Moewe or I covered while we were Fort Worth Star-Telegram stringers going to the University of North Texas in Denton from 1988 to 1991:

- Blood leaks from medical waste onto car's windshield

- Dog, squirrel disqualified as UNT homecoming candidates

A story I was hoping to find was one that Mary broke about a youth soccer player from Lewisville, Texas. The girl was so good in a playoff game that two dads from the opposing team demanded that referees conduct a "panty check" to confirm that she wasn't a boy. (Thankfully, this did not happen.)

The story, which went all over the planet, turns up on the Baltimore Sun. Mary got great quotes from the 10-year-old girl:

Natasha Dennis, a 4-foot-5-inch fourth-grader with short brown hair, admits to being boyish. "I hate dresses," she said.

Still, Natasha, who has changed her hairstyle, said she did not appreciate the men's accusations.

"I think they should go somewhere and check and see if they have anything between their ears," she said.

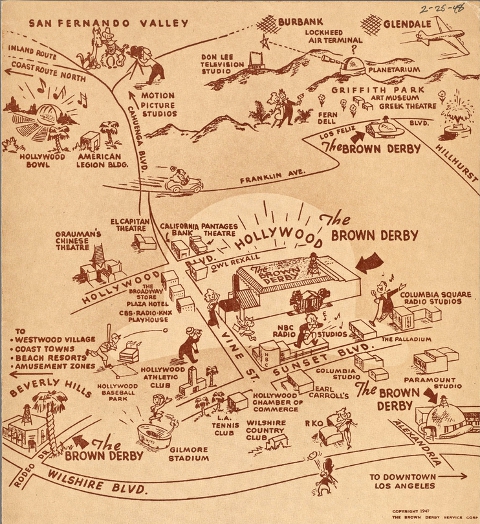

Now Serving: 45,000 Restaurant Menus

I found a cool resource today for writers of fiction set in past decades. The New York Public Library offers a historic restaurant menu database of 45,000 menus dating back to the 1840s. So far, 16,000 of the menus have been transcribed and volunteers are needed to help with the rest.

If you were thinking about eating at New York City's Louis Sherry restaurant at 300 Park Avenue in 1947, the smoked salmon appetizer, Catskill Mountain smoked turkey, fresh strawberry tartalette and Ballantine's XXX ale would set you back $4.60.

At the Brown Derby in Hollywood a year later, the famous Cobb Salad dish invented at the restaurant cost $1.50, is mixed at your table and has this description: "Chicken, crisp bacon, avocado, tomato, eggs, chives, Roquefort cheese, lettuce, romaine, watercress, chicory) all chopped fine served in chilled salad bowl with old-fashioned Derby dressing."

Media Can't Bury a Mass Shooter's Name

There's a lot of talk about how the media should adopt a self-imposed blackout on the name and life story of mass shooters. This makes a lot of sense because so many of these spree killers are motivated by a desire for notoriety. The media occasionally omits information for the greater good, such as when the names of rape victims and children accused of crimes are not reported.

Just this week dozens of media outlets hid the news that NBC foreign correspondent Richard Engel had been kidnapped in Syria along with a cameraman and producer:

A number of news operations in Turkey reported that Engel and a Turkish journalist were missing in Syria, and that story was picked up by the UK's Daily Mail and websites like Gawker. But, for the most part, NBC and an informal group of reporters and aid workers jaw-boned most of their colleagues into not following the story, arguing that reporting could put them in danger.

But when I read the suggestion that the Newtown killer's name be obscured to discourage future fame-seeking murderers, it makes me wonder whether people realize how uncontrollable the media environment has become.

There was a time when the media could have enforced a blackout policy successfully. Almost all of the news came from large professional outlets such as newspapers, wire services, TV stations and cable networks.

Today, those outlets are competing with millions of bloggers, online journalists, social network users and message board members, any of whom is capable of breaking a story that goes global.

The Newtown massacre is sending millions of people to their web browsers for more details. If the old media goliaths silenced all mention of the killer, the new media davids would stand to make an enormous windfall in traffic and ad revenue if they outed him. And nothing is capable of stopping them.

Twenty one years ago, the media hid the name of the woman who accused William Kennedy Smith of rape. She was still obscure enough that it was news six months later when she chose to reveal herself.

Nine years ago, the media hid the name of the woman who accused Kobe Bryant of rape. Her name was revealed by a no-name web site that received millions of hits. By the time she sued Bryant in civil court and some of the old media identified her a year later, it was a moot point.

What changed? In 1991 there wasn't a single web server in the entire United States.

Oklahoma City Time Capsule Buried in 1913

While doing some research in Google Books, I found an item in the May 1913 issue of Santa Fe Employees' Magazine that described the burial of a 100-year time capsule:

A unique service was held on April 22 at the Lutheran Church in Oklahoma City, Okla., when a copper chast containing phonograph records of speakers and singers, writings, musical compositions, daily newspapers and many other records of current events was buried. It is to remain intact until the year 2013, when it will be opened and the gap of a century will be bridged; and the future generation will hear the voices of our great men of today and read the writings and papers which we read today. The event was to celebrate the twenty-fourth anniversary of the opening of Oklahoma for settlement.

Sometimes time capsules are forgotten, but that's not the case here. The leaders of First Lutheran Church recently found the capsule with ground-penetrating radar and will be unveiling the contents of the Century Chest on April 22 as planned. The congregation gathered once a year at the time capsule's burial site and pledged to remember it. "They didn't want this to be forgotten, and it won't be," said Chad Williams of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

Remember Friedrich Franz III No More

Less than two weeks after she became the world's oldest person, Dina Manfredini died Monday at the age of 115 years and 257 days. Manfredini had been living at the Bishop Drumm Retirement Center in Johnston, Iowa.

Born in Pievepelago, Italy, on April 4, 1897, Manfredini became the oldest Italian and oldest immigrant who ever lived. She emigrated from Italy to Des Moines, Iowa, in 1920 with her husband Riccardo and raised four children, working at an ammunition factory during World War II and cleaning houses until she was 90. She lied about her age so people would still hire her. "I'm old, old lady, but I work. Work hard. I like work," she told the Des Moines Register in 2004 when she moved to a nursing home for the first time.

The newest oldest person, the Japanese man Jiroemon Kimura, was born 15 days after her on April 19, 1897.

With such a short jump forward, the line of oblivion doesn't gobble up much living history. But there's no longer a person who could have seen the UFO that reportedly crashed in Aurora, Texas, on April 17, 1897, northwest of Fort Worth, leaving behind the body of an extra-terrestrial pilot. An article in the Dallas Morning News two days later recounted the event:

It sailed directly over the public square, and when it reached the north part of town collided with Judge Proctor's windmill and went into pieces with a terrific explosion, scattering debris over several acres of ground, wrecking the windmill and water tank and destroying the judge's flower garden.

The pilot of the ship is supposed to have been the only one on board, and while his remains are badly disfigured, enough of the original has been picked up to show that he was not an inhabitant of this world.

Mr. T. J. Weems, the United States signal service officer at this place and an authority on astronomy, gives it as his opinion that he was a native of planet Mars.

There's also no one who could have known Friedrich Franz III, the second-to-last grand duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in Germany. The grand duke's death on April 10, 1897, was a subject of some confusion at the New York Times, as evidenced by these headlines: "The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin Shown to Have Committed Suicide" (April 13) and "The Grand Duke of Mecklenburg Schwerin Did Not Commit Suicide" (April 15).