The Danger of Employing Redskins as Movie Actors

Although it's getting a lot of flak from publishers and authors, Google Books is one of the most amazing contributions to world knowledge launched on the web in years. The ability to search the full text of thousands of books published prior to 1923 -- and hence in the public domain -- is amazing. I've been poking around it for a while, and I found something today while studying how Americans used the term "redskins" before Washington's NFL team chose that repulsive racist mascot in 1933.In the 1915 book Making the Movies, author Ernest Alfred Dench wrote a section giving advice to filmmakers on hiring Native Americans as actors. Here it is in full:

The Dangers of Employing Redskins as Movie Actors

It is only within the last two or three years that genuine Redskins have been employed in pictures. Before then these parts were taken by white actors made up for the occasion. But this method was not realistic enough to satisfy the progressive spirit of the producer.

The Red Indians who have been fortunate enough to secure permanent engagements with the several Western film companies are paid a salary that keeps them well provided with tobacco and their worshipped "fire water."

It might be thought that this would civilise them completely, but it has had a quite reverse effect, for the work affords them an opportunity to live their savage days over again, and they are not slow to take advantage of it.

They put their heart and soul into the work, especially in battles with the whites, and it is necessary to have armed guards watch over their movements for the least sign of treachery. They naturally object to acting in pictures where they are defeated, and it requires a good deal of coaxing to induce them to take on such objectionable parts.

Once a white player was seriously wounded when the Indians indulged in a bit too much realism with their clubs and tomahawks. After this activity they had their weapons padded to prevent further injurious use of them.

With all the precautions that are taken, the Redskins occasionally manage to smuggle real bullets into action; but happily they have always been detected in the nick of time, though on one occasion some cowboys had a narrow escape during the producing of a Bison film.

Even to-day a few white players specialise in Indian parts. They are pastmasters in such roles, for they have made a complete study of Indian life, and by clever make-up they are hard to tell from real redskins. They take leading parts, for which Indians are seldom adaptable.

To act as an Indian is the easiest thing possible, for the Redskin is practically motionless.

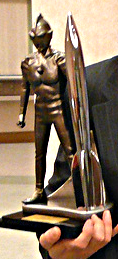

Predicting the Next Hugo Award-Winning Novel

For the last two years I've voted in the Hugo Awards, yearly literary honors for science fiction and fantasy (but mostly science fiction). I skipped the best novel category because I hadn't read most of the works, which is no fun at all since that's the biggest award. So when the 2010 Hugos are decided next spring, I'd like to have completed enough of the nominated novels to make an informed vote.

For the last two years I've voted in the Hugo Awards, yearly literary honors for science fiction and fantasy (but mostly science fiction). I skipped the best novel category because I hadn't read most of the works, which is no fun at all since that's the biggest award. So when the 2010 Hugos are decided next spring, I'd like to have completed enough of the nominated novels to make an informed vote.

This won't be easy, since I only read around one book a month. But after digging into the history of the awards, I've found that most best-novel nominated authors have been there before. If you're nominated for one novel, you have a pretty good shot that your next will be nominated as well. During the past decade, 34 out of 50 nominees were retreads. Here are the only first-timers over that period:

- 2000: J.K. Rowling

- 2001: Nalo Hopkinson, Ken McLeod, George R.R. Martin

- 2002: Neil Gaiman, China Mieville

- 2003: None

- 2004: Charles Stross

- 2005: Iain M. Banks, Susanna Clarke, Ian McDonald

- 2006: John Scalzi

- 2007: Michael F. Flynn, Naomi Novik, Peter Watts

- 2008: Michael Chabon

- 2009: Cory Doctorow

There are currently 68 living Hugo-nominated best novel authors, ranging in age from Naomi Novik at 36 to Frederik Pohl, who turns 90 next week on Nov. 26 and recently began his own blog. I put together an Amazon wish list of 22 novels by these authors coming out this year, leaving off some books that have no shot at all, such as book five in a genre series and every co-authored novel except for David Niven and Jerry Pournelle's Escape from Hell, the sequel to their 1976 Hugo-nominated novel Inferno.

I'm guessing that four out of five Hugo nominees and the eventual winner are on this list. I recently finished Transition by Iain M. Banks and began reading This is Not a Game by Walter Jon Williams, who was nominated 11 years ago for the novel City on Fire.

If you'd like to vote in the Hugos, all that's required is to become a supporting member of the next WorldCon science fiction convention before voting begins. A supporting membership in AussieCon 4, the 2010 WorldCon in Melbourne, Australia, currently costs $50 and can be upgraded later if you decide to attend. One cool perk of being a Hugo voter is that you're sent ebook copies of most nominated novels and many other nominated works for private review. Unfortunately, by the time they arrive you only have a few weeks in which to read them.

I'll be posting a review of Transition later this week.

Credit: The photo of a 2007 Hugo Award statue was derived from a photo taken by Doctorow available under a Creative Commons license.

They're Gonna Put Me in the Movies

I haven't seen the film Paranormal Activity, but I did fill out a web form requesting that it be shown in my town. That's apparently enough for me to earn a spot in the credits of the film when it comes out on DVD.

I got an email inviting me to add my name to the credits, and if you click the link the invitation will be extended to you as well.

After I filled out the form, I was shown a list of other people who are going to be credited. The list was 3,346 people long when I saw it, and included such film industry luminaries as Jeff "PocketPair77" Sugimura, Nisha Hookerpie, Michael "Shrek" Taylor, Daniel "Better Than Josh Levine" Newman and Jerry S 956 aka IVVI Wargasm. No, I don't know who those people are either.

It's not clear what my credited job is, but if there were any animals or insects involved in the production I could wrangle them.

I'm hoping this credit helps me get into IMDB.

Is Miss Farrell Crazy on Mad Men?

I've become an obsessed viewer of Mad Men this season, catching each episode on its first Sunday night airing and hitting the web afterwards to read reactions. The best place to do this is the blog of New Jersey Star-Ledger television critic Alan Sepinwall, who posts an extremely long critique of each episode that attracts hundreds of interesting comments.

For several weeks, Sepinwall's readers have been increasingly critical of Suzanne Farrell, the outspoken young teacher who is Don Draper's latest hoochie mama. They think she's "cuckoo bananas" and a Fatal Attraction waiting to happen, which I find to be a weird reaction.

I posted a comment along those lines Sunday night, asking this question, "When did an assertive woman who is open and direct about her feelings and clear about her needs equate to crazy? Particularly in the world of Mad Men where the cost of repression is made so abundantly clear."

Sepinwall responded: "I think the drunk-dialing scene in 'The Fog' and the eclipse scene in 'Seven Twenty Three' provided enough in-show evidence for people to at least wonder if something is off about Miss Farrell, if not know for sure that there is."

Though subsequent episodes may prove me wrong, I think Farrell makes viewers tense because she's more self-aware than any of Draper's previous conquests. This trait makes it harder to believe that once they're over, she'll go quietly into that good night.

But it does not make her a bunny boiler. Farrell has never done anything that would call her sanity into question more than, say, masquerading as another man and continuously pursuing empty sexual relationships that could destroy your family.

If you show up next Sunday night on Sepinwall's blog, make note of his rules: Don't post spoilers or talk at all about the preview of the next episode.

Readers Have Never Paid for the News

British commentator Libby Purves has become the latest veteran journalist to declare that Internet freeloaders are ruining the newspaper business and they need to start paying for the media they consume, or else trained professionals like her will take their inverted pyramid and go home. In response to the switch of London's Evening Standard to free circulation, Purves writes:

Call me a reactionary, call me a Murdoch lackey, but the fact is that, after a vague flirtation with the concept that "information wants to be free" and years of internet surfing, I feel a sense of revolt.

It's been fun: like a jammed fruit machine spewing free tokens or a whisky-galore shipwreck. But it's got to stop. Content -- whether music, films, pictures, news or prose -- can't be free and flourish. The music and movie industries are fighting: journalism, after the ego trip of gaining millions of online readers, is following. It has to. There is no alternative.

The labourer is worthy of his hire, time is money, pay peanuts and you get monkeys. Pay nothing and you get dumb (or worse, venal) monkeys. Nothing costs nothing.

Whenever I read an unhappy rant like this from a journalist, it makes me wonder how they could know so little about where their paycheck is coming from. Newspaper readers have never paid for their news, outside of rare exceptions like the Wall Street Journal and trade publications such as Variety. Daily newspapers derive most of their revenue from advertisers. Lauren Rich Fine, a former newspaper industry analyst with Merrill Lynch, estimated that historically, subscriptions generated 20 percent of a newspaper's revenue and the other 80 percent came from classifieds and display advertising.

So back in the glory days of newspapers before the Internet ruined everything, readers were getting their journalism at a steep discount paid for by advertisers. Newspapers were the biggest game in town for local classifieds and department store ads and papers enjoyed extremely fat profit margins because of it. But if there's one thing that a journalist should be in a position to know, it's the fact that times change.

Even today, Internet freeloaders aren't getting their news for free. Nine different ads are running on the page that includes Purves' Times of London column.

The real issue here is that online ads aren't generating the kind of revenue that other ads did for decades, so it's an extremely rough time for the industry. But placing the blame on readers for being cheapskates is extremely misguided. We've always gotten the news at a price much lower than the cost of reporting it.

Credits: The photo of the Evening Standard van by Oxyman is available under a Creative Commons license.

Dear Derek Powazek: SEO is a Legitimate Profession

I'm a huge fan of the web designer and magazine publisher Derek Powazek, but I couldn't disagree more with his rant that calls all search engine optimization (SEO) a con game:

Search Engine Optimization is not a legitimate form of marketing. It should not be undertaken by people with brains or souls. If someone charges you for SEO, you have been conned. ...

The problem with SEO is that the good advice is obvious, the rest doesn't work, and it's poisoning the web.

I tried to respond on his blog, but he's closed comments. Saying that good SEO is obvious is like saying that good web design is obvious. Lumping all SEO consultants with scammers and spammers is unfair to thousands of people who do that work honorably.

The kinds of things he's saying about SEO were being said about blogs back when mass-audience tools like Blogger and Movable Type helped popularize the medium. The publishing style of blogs -- short frequent items with category links and heavy link exchange among bloggers -- had a considerable SEO benefit and helped blogs rise to the top of search results, making a lot of static-site publishers angry.

The kinds of things he's saying about SEO were being said about blogs back when mass-audience tools like Blogger and Movable Type helped popularize the medium. The publishing style of blogs -- short frequent items with category links and heavy link exchange among bloggers -- had a considerable SEO benefit and helped blogs rise to the top of search results, making a lot of static-site publishers angry.

If I'd been able to comment, I would have posed this question to Derek: Have you ever tried to help a small business launch a new site and be discovered by potential customers on search engines? It's a difficult task that's vital to their livelihood. The black-hat junk that he slams makes it even harder for them.

Good SEO is essential to these businesses, which aren't in a position to simply "Make something great. Tell people about it. Do it again," since they are not web auteurs with a 14-year track record of launching great sites. Try explaining to a company that provides environmental cleanup services across two states that it doesn't need SEO because it just has to create something cool and tell people. Or a local chiropractor. Companies throw hundreds or even thousands of dollars at yellow-page publishers for a single ad because their need to be found by customers is so strong. A lot of people never look at those tree-killing phonebooks anymore. They use Google.

As obvious as Derek believes SEO to be, he missed one of the most basic techniques by omitting a title in the URL of his blog posts.

I'm not an SEO consultant, but I've learned about the techniques over the years because I run a one-man shop that can't afford advertising. Most SEO techniques are about learning how Google works, not trying to game it inappropriately. The first thing I would hire, if my business could afford it, is an expert in SEO. That talent pays for itself more quickly than any other skill in web publishing.

Photo of Derek Powazek taken by Isriya Paireepairit and redistributed under a Creative Commons license.

Saving Bandwidth on RSS Feed Details

With the current interest in rssCloud and PubSubHubbub (PuSH), I've been thinking about all the bandwidth that's consumed by the RSS elements that describe the feed. When a client requests an RSS feed 10 times in one day, it gets the basic details of the feed over and over again. When clients request the Workbench feed, they get 1,800 characters containing optional RSS elements that I haven't changed in years, except for the PuSH element I added last month. Workbench has 1,900 feed subscribers, so if they average 10 checks a day, they're consuming 32 megabytes every day on information they know already.

James Holderness directed me to RFC3229+feed, a method to request partial RSS feeds that omit elements that a client has already seen. That's useful and has been adopted by some feed publishers and clients, but as far as I can determine, the approach still sends all of the channel elements that describe the feed itself. I wanted to float an idea here to see if it would be useful:

<rssboard:feedDetails>

http://ekzemplo.com/feedinfo.rss

</rssboard:feedDetails>

This channel-level RSS element identifies a URL that contains the full details about the feed. The details would be expressed as an RSS feed without any item elements.

An optional ttl attribute could contain the number of days the publisher would like clients to cache the information before checking it again:

<rssboard:feedDetails ttl="30">

http://ekzemplo.com/feedinfo.rss

</rssboard:feedDetails>

A feed publisher who wished to make use of this could move all channel elements except for title, link, description and atom:link to the detail URL. Title, link and description are required in RSS, and atom:link identifies the feed's URL so it can't be moved.