Kickin' It Old School with Microsoft Word 97

I began a new book this week on Java programming for beginners. I haven't been doing much computer book writing for a couple years, so I no longer had an installed copy of Microsoft Word 97, the version of the software my publisher uses to draft manuscripts. Word 2007 can save files in 97 format, but it doesn't support the publisher's custom styles, so I decided to install Word 97 on Vista.

I began a new book this week on Java programming for beginners. I haven't been doing much computer book writing for a couple years, so I no longer had an installed copy of Microsoft Word 97, the version of the software my publisher uses to draft manuscripts. Word 2007 can save files in 97 format, but it doesn't support the publisher's custom styles, so I decided to install Word 97 on Vista.

Huge mistake.

Word 97 appeared to install properly, but when I installed some other Microsoft software afterward, it removed files that Word 97 requires to run. Now the program reports a registry error every time it runs and Vista won't uninstall it or install a new copy.

After considering other options, I installed a trial version of VMware Workstation, $188 software that creates virtual computers in which you can run other operating systems. You run the simulated computer in its own window after deciding how much disk space and memory to allocate to it, and it acts like it's an entire computer. After setting up one of these virtual systems, you can clone it, suspend it and run it remotely over the Internet.

Using VMware, I created a new virtual Windows XP system where I can run Word 97 and the other software required to write my book. As far as I know, this Pinocchio virtual computer thinks it's a real PC.

Because Microsoft is run by sadists, I had to install Windows 98 before I could install a Windows XP upgrade. It was weird to step back in time and see the Microsoft channel bar, an early stab at web syndication that predated RSS. During installation, Windows 98 also touts its support for USENET newsgroups. Kids today don't know how good they got it. In my day, if we wanted to see celebrities naked, we had to know how to UUdecode.

If anyone has any experience with VMware, I'd like to hear how well it works. My biggest concern is whether anything I do inside the virtual computer can adversely impact the real Vista system it runs on. I want virtual computers that I can destroy with impunity by running buggy beta software and other dodgy programs that don't get along with each other. I end up doing that a lot in the course of writing a book.

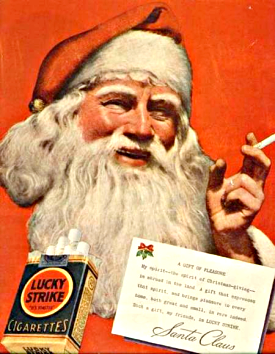

'Mad Men': Smoke, Smoke, Smoke That Cigarette

I'm catching up on Mad Men by watching the first season on DVD. I find the show's atmosphere amazing, both in terms of the characters at the ad agency and the 1960 setting they inhabit. I can't recall a TV series where the sets have been so immaculately well-designed. The offices, bars, apartments and homes are so engrossing that at times I wish the characters would get out of the way so I could see them better.

Part of the appeal is nostalgia. When I was a young child in the early '70s my mother worked in Dallas as a secretary for the ad agency TracyLocke, and my recollection of visits there matches the look of Sterling Cooper. My memories are more pleasant than hers, since I didn't have to work there. One of the workers kept a bowl of SweeTarts fully stocked at his desk, and every visit I'd make sure to hit that bowl at least twice for everything I could carry.

Instead of burning through the episodes like a junkie, as I did recently with Weeds, I'm going to take my time with Mad Men. "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes," the pilot episode, begins with senior ad man Donald Draper struggling to come up with a new campaign for Lucky Strike cigarettes. The government has begun cracking down on tobacco companies that make bogus health claims in their advertising, just as the risks of lung cancer to smokers are becoming a major public concern.

Reader's Digest is mentioned during the episode because of an article scaring people about smoking. A detailed synopsis on TV.Com reveals that the show refers to a real article, "The Growing Horror of Lung Cancer," that appeared in March 1959.

I found the article in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, an archive of 10 million documents from tobacco companies about the sales and safety of their product. Reading the Reader's Digest article provides an interesting -- and horrifying -- perspective on the first days of the lung cancer epidemic:

I found the article in the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, an archive of 10 million documents from tobacco companies about the sales and safety of their product. Reading the Reader's Digest article provides an interesting -- and horrifying -- perspective on the first days of the lung cancer epidemic:

Of 100 people who get lung cancer today, the physician told him, 45 will be inoperable by the time they consult a doctor, their cancer so widespread that surgery will be futile. Chests of the remaining 55 will be opened. This is drastic surgery and as many as 11 of the 55 patients may die of it. Inspection of the chest cavity will often give clear evidence of cancer spread, possibly even to the heart itself. In such cases the surgeon may leave the lung untouched and simply close the wound. These patients -- perhaps 12 -- will be dead in a few months.

By now the original 100 has dwindled to 32 patients who are operable. The surgeon removes all or part of the diseased lung and prays that no cancer seeds have been left behind. But in a distressingly large percentage of cases, clusters of these cells lurk in hidden recesses, to continue their growth. According to present statistics, only 5 of the 32 patients who survive the operation will be alive -- and presumably cured -- at the end of five years. Thus the score stands: 5 survivors out of 100 victims.

The article, which makes one smoker's pneumonectomy surgery sound nightmarishly medieval, is a pretty amazing read with five decades of hindsight. Heavy smokers were learning for the first time that they faced a high likelihood of lung cancer.

A few years ago, lung cancer was a medical problem of no consequence. A survey of world medical literature in 1912 showed a total of only 347 cases reported. Today annual deaths are measured by the tens of thousands. Tomorrow?

"It frightens me to think of what is going to happen in another decade when our present smoking habits catch up to us," says Dr. Ochsner.

Ochsner was Alton Ochsner, a famous surgeon whose clinic was one of the first to link cancer and cigarettes. As a young medical intern in the '20s he was once invited to witness a lung surgery operation on the grounds he might never see one again. He didn't for another 17 years, but then began getting numerous cases of World War I vets who had taken up smoking as young men.

Decades after the health risks of smoking became crystal clear, lung cancer continues to kill 1.1 million people a year, thanks in part to generations of ad execs like the protagonists of Mad Men.

Times Gives Aaron Swartz Props for RSS

In a discussion about journalism on venture capitalist Fred Wilson's blog, Dave Winer writes:

... professionals make plenty of these kinds of mistakes. For example last week the esteemed NY Times said RSS was software and that it was co-written by a 14-year old on a mail list. It is neither of those things.

They never called me to check it out.

The 14-year-old he references is Aaron Swartz, who got some nice press recently from the Times for an incredibly ballsy stunt he pulled to promote public access to government documents. Swartz used a scraping program to surreptitiously download 19 million pages of court documents -- totaling 780 gigabytes of data -- over the course of six weeks during a free trial of the government database Pacer. The data was sent to the non-profit Public.Resource.Org.

The Lede, a Times blog, described Swartz's role in RSS:

In the technology world, Mr. Swartz is kind of a big deal, as the saying goes. At the age of 14, he had a hand in writing RSS, the now-ubiquitous software used to syndicate everything from blog posts to news headlines directly to subscribers.

Winer believes credit for RSS is doled out under Highlander rules -- all challengers must be decapitated, for "in the end, there can be only one!" But The Times is correct to credit Swartz for his important role in RSS. When he was still in junior high school, Swartz became one of the lead authors of the RSS 1.0 specification, the version of the syndication format that employs RDF. He also has hosted the specification for the past eight years.

ABC Cancels 'Life on Mars'

ABC has cancelled Life on Mars, the surreal crime drama that dropped a New York cop 35 years into the past, reports Michael Ausiello of Entertainment Weekly:

Multiple sources are confirming that ABC has canceled my beloved Life on Mars. Per an insider, the network recently advised the show's producers that it would not be ordering a second season. The heads-up will allow them to make this year's season finale a series finale, thus leaving no questions unanswered. And unlike Pushing Daisies, Dirty Sexy Money, Eli Stone, etc., all indications are that ABC will actually air this series finale. We're making progress, people!

This is good news for my TV Deathpool but bad news for me personally. Life on Mars was my favorite show of the new TV season. The cast is great -- Jason O'Mara, Gretchen Mol, Michael Imperioli and Harvey Keitel in his first TV series -- and the 1973 period details were completely funkadelic. The series convinced me that the '70s were not the musical black hole I thought they were, working songs both popular and obscure into the proceedings. Recent episodes featured Harry Nilsson's Spaceman, The Kinks' Supersonic Rocket Ship and Marion Black's Come On and Gettit.

That's some pretty impressive James Brown sex grunting from Black, a performer who's so forgotten today that his family was surprised and proud to find something about him on the web. Television remembers him, though -- another one of his songs, Who Knows, showed up on an episode of Weeds.

The Life on Mars finale ought to clear up whether Det. Sam Tyler's trip was the result of time travel, a coma, the afterlife or nanobots living up his nose. I was hoping we wouldn't find out the answer for a couple years.

eHarmony's Tanyalee Does Not Oppose Gay Marriage

Tanyalee Pearson, one half of the eHarmony TV commercial couple I wrote about in January, has posted a comment on Workbench:

I would like to inform you that My husband Joshua wrote a blog about prop 8 back in Oct.

She also wrote a longer response on a blog devoted to eHarmony:

This post we oppose gay marriage, Now first off ... Joshua wrote the whole prop 8 back in oct. I tanyalee did not write the comment, I do love my husband, I have a lot friends that are gay, I love them all, they all are people, and don't judge them at all. I lived in Hollywood for a long time, and 90% of my friends were gay ... I do not judge, not is not for me to do, I think we have was too much judging going on in this world, I don't need to be a part of that. I know how it feels to be judged people have been doing that to joshua and I a lot from the moment we met ...

Pearson's comments could be fake, but the blog post to which they refer was deleted from the couple's blog within the last seven days, which suggests they are legit. The post can still be retrieved from Google's cache and was reprinted in full on Survivor Sucks.

So it appears that I reached the wrong conclusion earlier about who wrote the anti-gay marriage post on their shared blog. Instead of being written by the artistic boutique owner, the biblical argument for Proposition 8 was penned by the "geeky chemist" whose MySpace motto is "come on jesus!" I should have realized this might be the case, since the guy's church prescreens applicants to its School of Supernatural Worship with the questions "Have you ever been involved in homosexuality or lesbianism?" and "If yes, how long since last involvement?" (To any reader who might face these questions in the future, anything that happened in college when you were really drunk does not count.)

So my apologies to Tanyalee, who does not oppose the right of her 90 percent gay friends to marry, thus putting her in strong disagreement with her husband.

Unless I'm mistaken, Joshua and Tanyalee now have only 28 degrees of compatibility.

Newspapers Have Been Dying Since the '50s

Debra J. Saunders has an impassioned rant in today's San Francisco Chronicle about how we'll all be sorry when newspapers are dead:

News stories do not sprout up like Jack's bean stalk on the Internet. To produce news, you need professionals who understand the standards needed to research, report and write on what happened. If newspapers die, reliable information dries up. ...

I wonder who will be around in five years to cover stories. Or what talk radio will talk about when hosts can't just siphon from carefully researched stories, because they never were written.

Saunders blames the web and ideologically motivated haters for the demise of newspapers, but she ignores the fact that major dailies have been dying for decades, long before the Internet came along. Back in the '50s when Saunders was a child, the legendary journalist A.J. Liebling devoted numerous New Yorker articles to the sad demise of major papers and the societal hole that each left behind when the presses rolled to a halt. The industry has been dying for as long as many of us have been alive. Multiple newspaper towns became two paper towns, morning and afternoon. Two-paper towns became single-paper towns, usually when one paper killed the other. I can still remember where I was on Dec. 8, 1991, when I heard the news that the Dallas Times-Herald had been bought for $55 million and immediately shut down by the rival Dallas Morning-News. When a paper dies, a sizeable chunk of its readership doesn't move to another paper. People just break the habit. Even though half the reporters in town were gone, I don't recall any stories in the News back then lamenting the stories that would never be written.

Now that even the last paper standing in many cities is at risk of closure, we're supposed to agonize over the loss in a way that those papers never mourned the death of their cross-town rivals. Does Saunders realize that every paper left in this country has been cutting costs by dropping experienced reporters and limiting beats as fast as it can? The reporting she thinks we'll miss -- enterprise stories, investigative reports and government watchdog news -- is already a shadow of its former self. Former reporter David Simon devoted the final season of his TV series The Wire to the decimation of his old employer, the Baltimore Sun. By the end his alter ego, a long-time city editor named Gus, had been relegated to the copy desk with his most knowledgeable reporters shown the door. Most of the experienced reporters and editors who do the kind of journalism Saunders celebrates aren't in the newsroom any more. They got fired, bought out or took early retirement.

Saunders also ignores the role that massive debt has played in the economic troubles of our remaining dailies. Newspaper chains and other big media corporations have been gobbling up papers for years by borrowing to the hilt, counting on future profits to stay fat. A July 2008 Bloomberg article shows that the newspaper chains were overleveraged even before the current economic bust. The blogosphere and talk radio did not make the Gordon Gekkos who own newspapers saddle their publications with crushing piles of debt that require constant cost-cutting to finance.

I love newspapers. I began reading the Times-Herald when I was eight years old, delivered papers as a teen, majored in journalism, married a journalist and got my first job out of college at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. I will read them until the last one folds.

But if we really begin to see major cities left without a single daily newspaper, I believe that it will create opportunities for leaner, more focused, more Internet-savvy media operations. There also will be more altruistic efforts to cover the news, like what's happening in Southern California with the non-profit Voice of San Diego.

Voice of San Diego is a four-year-old, 11-member news outlet that's funded by charitable foundations and reader donations. It began with the mission to "consistently deliver ground-breaking investigative journalism for the San Diego region" and "increase civic participation by giving citizens the knowledge and in-depth analysis necessary to become advocates for good government and social progress."

I don't believe there will be no news without newspapers. If journalism meets an essential need for an informed citizenry, something else will arise in their place to meet that need.

TechCrunch Runs Bogus Last.fm Rumor

![]() Late Friday, TechCrunch ran a single-sourced allegation that the CBS-owned music-recommendation service Last.fm had handed over user data to the RIAA for use in illegal file-sharing lawsuits:

Late Friday, TechCrunch ran a single-sourced allegation that the CBS-owned music-recommendation service Last.fm had handed over user data to the RIAA for use in illegal file-sharing lawsuits:

... word is going around that the RIAA asked social music service Last.fm for data about its user's listening habits to find people with unreleased tracks on their computers. And Last.fm, which is owned by CBS, actually handed the data over to the RIAA. According to a tip we received:

I heard from an irate friend who works at CBS that last.fm recently provided the RIAA with a giant dump of user data to track down people who are scrobbling unreleased tracks. As word spread numerous employees at last.fm were up in arms because the data collected (a) can be used to identify individuals and (b) will likely be shared with 3rd parties that have relationships with the RIAA.

Reporter Erick Schonfeld's story had several red flags that it might be bogus, including the weasely phrase "word is going around" and the fact that he got it secondhand from a friend of a CBS employee, not directly from someone at CBS, Last.fm or the RIAA. But the allegation was so spectacularly damaging that it spread quickly across the web, scaring users into deleting their Last.fm accounts. They had good reason to be concerned. Users running Last.fm's AudioScrobbler software tell the service every song they play on their computers. If you're playing pirated songs from an album not yet released, and they RIAA finds this out, its lawyers could sue you so hard your grandmother gets served.

Last.fm founder Richard Jones says that TechCrunch is full of bleep:

On Friday night a technology blog called Techcrunch posted a vicious and completely false rumor about us: that Last.fm handed data to the RIAA so they could track who's been listening to the "leaked" U2 album.

I denied it vehemently on the Techcrunch article, as did several other Last.fm staffers. We denied it in the Last.fm forums, on twitter, via email -- basically we denied it to anyone that would listen, and now we're denying it on our blog.

Schonfeld has updated the story several times in response to angry pushback, digging a deeper hole each time:

From the very beginning, I've presented this story for what it is: a rumor. Despite my attempts to corroborate it and the subsequent detail I've been able to gather, I still don't have enough information to determine whether it is absolutely true. But I still don't have enough information to determine that it is absolutely false either.

Calling something a rumor doesn't give journalists a free pass -- spreading a bogus rumor can have the same consequences as passing along bogus information, and in either case the reporter owes readers an explanation of why the story was published. TechCrunch needs to explain why it trusted the friend of a CBS employee with a secondhand tip, whether anyone tried to contact the employee to corroborate the claim and whether it was wrong to run such a damaging story without at least one source who had direct knowledge of the alleged data transfer.

Time magazine recently declared TechCrunch one of the most overrated blogs, stating that the the site has become "irrelevant." That judgment isn't borne out by the traffic, but this story shows one reason why TechCrunch has lost some of its rep. Like other pro blogs constantly churning out new posts, TechCrunch is more concerned with being first than being right.