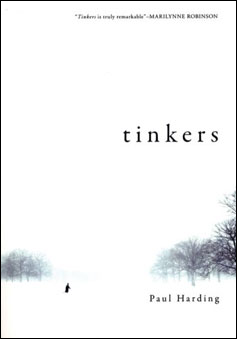

Review: 'Tinkers' by Paul Harding

This year's Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Tinkers by Paul Harding, is one of the best I've read in years. The slim 191-page book is about the last eight days of dying clock repairman George Washington Crosby, whose hallucinating mind wanders across time in his final hours, stopping at disordered points in his life and that of his father.

The first novel by Harding, Tinkers was rejected by numerous publishers and sat in a drawer for several years before it found a home at Bellevue Literary Press, an obscure non-profit publisher based in New York's Bellevue Hospital. It's the first book from a small press to win the Pulitzer since John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces in 1981.

The first novel by Harding, Tinkers was rejected by numerous publishers and sat in a drawer for several years before it found a home at Bellevue Literary Press, an obscure non-profit publisher based in New York's Bellevue Hospital. It's the first book from a small press to win the Pulitzer since John Kennedy Toole's A Confederacy of Dunces in 1981.

I don't often like awardbait -- difficult literary novels with spare plots seemingly tailored for award consideration -- but the language of Tinkers is as exquisite as a T.S. Eliot poem. Harding is at his most evocative when describing the workings of an antique clock or the natural wonder of the New England countryside, yet the entire book is written with an tinkerer's eye towards the world. There may never be a more eyebrow-curling description of halitosis than when George's father Howard pulls the tooth of a suffering hermit who buys from his tinker's wagon: "A breeze caught the hermit's breath and Howard gasped and saw visions of slaughter-houses and dead pets under porches." When George witnesses his father's epileptic seizure at the dinner table on Christmas Day, it's a perfectly described moment of absolute terror -- and you can see why he's taking it to the grave.

At times, Tinkers wanders into pure existential reverie, like these thoughts from George's father as he drags his wagon of goods from one rural homestead to another:

Your cold mornings are filled with the heartache about the fact that although we are not at ease in this world, it is all we have, that it is ours but that it is full of strife, so that all we can call our own is strife; but even that is better than nothing at all, isn't it? And as you split frost-laced wood with numb hands, rejoice that your uncertainty is God's will and His grace toward you and that that is beautiful, and part of a greater certainty, as your own father always said in his sermons to you at home. And as the ax bites into the wood, be comforted in the fact that the ache in your heart and the confusion in your soul means that you are still alive, still human, and still open to the beauty of the world, even though you have done nothing to deserve it. And when you resent the ache in your heart, remember: You will be dead and buried soon enough.

I wasn't sure about this novel until I was 50 pages in, and even briefly considered abandoning it for fare more light than an old man's deathbed vigil. The cumulative impact of passage after passage like the above convinced me that Tinkers was a masterwork that would be cherished for generations, like a centuries-old grandfather clock.

Related posts:

- The New York Times, which did not review Tinkers, tells the story of its publication

Comments

You know you've arrived when the custom upholstered furniture guy gives you the thumbs up.

If my work reaches just one spammer working in a third-world captcha-breaking sweat shop, it's worth it.

I hear it's part of a trilogy - the next novel is called "Evers."

"Time is the substance from which I am made. Time is a river which carries me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger that devours me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire that consumes me, but I am the fire."

Jorge Luis Borges

"I hear it's part of a trilogy - the next novel is called 'Evers.'"

Nice. I would take a "Chance" on that. ;)

Surely it is his very best book, so far

Add a Comment

All comments are moderated before publication. These HTML tags are permitted: <p>, <b>, <i>, <a>, and <blockquote>. This site is protected by reCAPTCHA (for which the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply).